| #security | |||

Chrome's SSL Bypass Cheatcode |

|||

This is Unsafe

If you type thisisunsafe on a Chrome SSL error page, Chrome will bypass the error and load the page for you.

Try it yourself here: https://expired.badssl.com/

There’s no textbox to type into, just type thisisunsafe blindly with the page in focus.

TIP: To revert the bypass, click the “Not Secure” button in the URL bar and then click “Turn on warnings.”

History of the Bypass Code

My first reaction upon discovering thisisunsafe was one of delight! I was flooded with memories of trying ↑ ↑ ↓ ↓ ← → ← → B A on every Playstation game I had as a kid (see Konami Code).

By why does Chrome have a cheatcode?

Like Tomb Raider searching for ancient artifacts, my sense of wonder led me to dig through history of Chromium to try and find out how this code came to be. I was curious to know if it was a joke, a mistake, or something else entirely.

Here’s what I found.

Danger (2014)

https://codereview.chromium.org/480393002/patch/60001/70017

/*

* This allows errors to be skippped [sic] by typing "danger" into the page.

* @param {string} e The key that was just pressed.

*/

function handleKeypress(e) {

var BYPASS_SEQUENCE = 'danger';

if (BYPASS_SEQUENCE.charCodeAt(keyPressState) == e.keyCode) {

keyPressState++;

if (keyPressState == BYPASS_SEQUENCE.length) {

sendCommand(CMD_PROCEED);

keyPressState = 0;

}

} else {

keyPressState = 0;

}

}

The bypass code was first introduced in 2014. Originally set to “danger,” it was newly created part of a larger piece of work related to DRY-ing up duplication in chrome/browser/resources/safe_browsing/ and chrome/browser/resources/ssl/.

See: Aug 11, 2014 18:03UTC - Chromium Issue #41125304:

Unfortunately, the reason it was added doesn’t appear to have been documented. My guess is that developers needed a convenient way to bypass SSL errors during the rise of HTTPS adoption and enforcement.

Bad Idea (2015)

https://codereview.chromium.org/1416273004/patch/1/10001.

--- a/components/security_interstitials/core/browser/resources/interstitial_v2.js

+++ b/components/security_interstitials/core/browser/resources/interstitial_v2.js

@@ -40,7 +40,7 @@ function sendCommand(cmd) {

* @param {string} e The key that was just pressed.

*/

function handleKeypress(e) {

- var BYPASS_SEQUENCE = 'danger';

+ var BYPASS_SEQUENCE = 'badidea';

if (BYPASS_SEQUENCE.charCodeAt(keyPressState) == e.keyCode) {

keyPressState++;

if (keyPressState == BYPASS_SEQUENCE.length) {

A year later, in 2015, the BYPASS_SEQUENCE was changed to badidea. Like before, there’s little evidence left to understand the intention behind the changes.

However, as we’ll see, later changes were made due to concerns around the bypass code’s popularity and misuse, so it seems likely that the change to badidea was changed made for similar reasons.

Interestingly, in 2014, Google published a paper entitled Experimenting At Scale With Google Chrome’s SSL Warning, where authors experimented with ways to reduce the number of users who bypassed SSL warnings via the UI.

Our goal in this work is to decrease the number of users who click through the Google Chrome SSL warning… We investigate several factors that could be responsible: the use of imagery, extra steps before the user can proceed, and style choices.

Felt, Adrienne Porter, et al. “Experimenting At Scale With Google Chrome’s SSL Warning.” (2014).

This is not Safe (2018)

--- a/components/security_interstitials/core/browser/resources/interstitial_large.js

+++ b/components/security_interstitials/core/browser/resources/interstitial_large.js

@@ -13,7 +13,7 @@

* @param {string} e The key that was just pressed.

*/

function handleKeypress(e) {

- var BYPASS_SEQUENCE = 'badidea';

+ var BYPASS_SEQUENCE = 'thisisnotsafe';

if (BYPASS_SEQUENCE.charCodeAt(keyPressState) == e.keyCode) {

keyPressState++;

if (keyPressState == BYPASS_SEQUENCE.length) {

On Januay 03, 2018, the bypass code was updated again, this time to thisisnotsafe.

Unlike before, the code was changed explicitly due to concern around the growing popularity of being able to bypass SSL warnings in Chrome using the bypass code.

The security interstitial bypass keyword hasn’t changed in two years and awareness of the bypass has been increased in blogs and social media. Rotate the keyword to help prevent misuse.

Based on the source code, the bypass code was only intended for testing and not for general use. The click-through UI or Chrome flags were abled to be monitored for patterns, like we saw in the 2014 paper. Use of the bypass code, however, doesn’t seem to have been tracked.

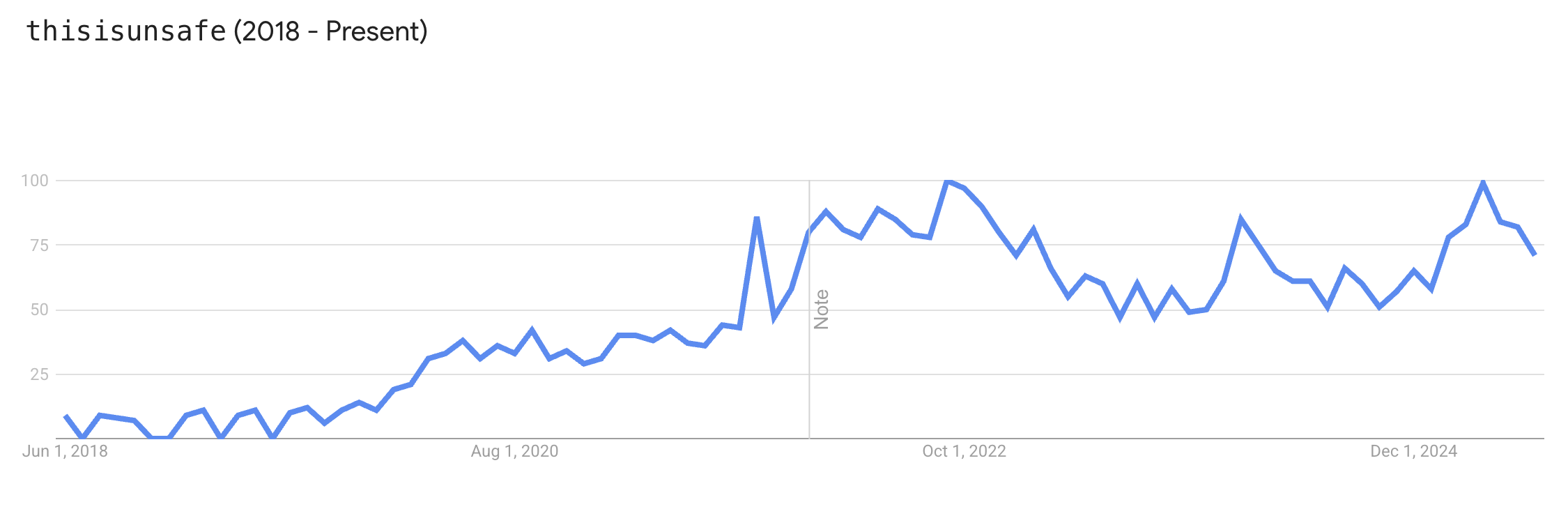

dGhpc2lzdW5zYWZl (2018 - Present)

--- a/components/security_interstitials/core/browser/resources/interstitial_large.js

+++ b/components/security_interstitials/core/browser/resources/interstitial_large.js

@@ -13,7 +13,10 @@

* @param {string} e The key that was just pressed.

*/

function handleKeypress(e) {

- var BYPASS_SEQUENCE = 'thisisnotsafe';

+ // HTTPS errors are serious and should not be ignored. For testing purposes,

+ // other approaches are both safer and have fewer side-effects.

+ // See https://goo.gl/ZcZixP for more details.

+ var BYPASS_SEQUENCE = window.atob('dGhpc2lzdW5zYWZl');

if (BYPASS_SEQUENCE.charCodeAt(keyPressState) == e.keyCode) {

keyPressState++;

if (keyPressState == BYPASS_SEQUENCE.length) {

Just a few days later, on January 10, 2018, the bypass code was changed once again:

thisisnotesafe was changed to dGhpc2lzdW5zYWZl, in what I believe was an attempt at obfuscation.

$ echo dGhpc2lzdW5zYWZl | base64 -d

thisisunsafe

This made no difference in terms of functionality; the code was simply base64 encoded, and the window.atob function was used to decode it back to its original form.

Along with this code change, the Chromium developers added a comment linking to a public document titled: Deprecating Powerful Features on Insecure Origins.

Though the document made no mention of the bypass code itself, it included instructions for how to bypass SSL errors during development and testing:

You can use

chrome://flags/#unsafely-treat-insecure-origin-as-secureto run Chrome, or use the--unsafely-treat-insecure-origin-as-secure="http://example.com"flag (replacing"example.com"with the origin you actually want to test), which will treat that origin as secure for this session.

I presume this is what was meant by the “…other approaches are both safer and have fewer side-effects,” comment in the code snippet above.

Is this Unsafe?

Despite all the digging, I am still unaware of the intention behind the bypass code’s original creation.

/**

* This allows errors to be skippped [sic] by typing a secret phrase into the page.

* @param {string} e The key that was just pressed.

*/

function handleKeypress(e) {

// HTTPS errors are serious and should not be ignored. For testing purposes,

// other approaches are both safer and have fewer side-effects.

// See https://goo.gl/ZcZixP for more details.

const BYPASS_SEQUENCE = window.atob('dGhpc2lzdW5zYWZl');

if (BYPASS_SEQUENCE.charCodeAt(keyPressState) === e.keyCode) {

keyPressState++;

if (keyPressState === BYPASS_SEQUENCE.length) {

sendCommand(SecurityInterstitialCommandId.CMD_PROCEED);

keyPressState = 0;

}

} else {

keyPressState = 0;

}

}

As of July 2025, the bypass (along with the skippped typo) has remained unchanged. You can see it in the latest version: Chromium (140.0.7301.1).

It still shows up in blogs and social media posts today (though none of them do a deep dive like this one!), which is how I stumbled upon it.

What may have started as a convenience for developers, later became a point of concern due to its potential misuse. The change to base64 encoding was likely an attempt to obscure the code from casual users or code scanners, but it is by no means a secret.

The rise of HTTPS enforcement has been a net-positive for the web, but it’s hard to articulate the risks of broken SSL to everyday users and why they shouldn’t simply ignore it.

Is it the job of a browser to keep users safe? Even if one could argue that web access shouldn’t be gated by coporations on the basis of security, the enforcement of HTTPS has undoubtedly incentivized web developers to adopt better security practices.

What do you think?