| #rust | |||

Ownership in Rust, Part 2It’s still not my problem. |

|||

Checkout Ownership in Rust, Part 1.

When we looked at ownership in Rust last time, we looked at how Rust uses scope to determine when a resource/data in memory should be *dropped *or freed.

We saw that for types that have a “copy trait,” (i.e. types whose data can be stored on the stack), the ownership model behaves similarly to other languages that may use a different paradigm, like garbage collection. But for types without this trait, we needed to be more conscious of the ownership rules.

Despite the design compromises that ownership may introduce, it makes up for it with flexibility, explicitness, and safety.

Ownership and Functions

fn main() {

let string = "Hello, World!";

println("{:p}", string); // 0x5652d704aa80

foo(string);

}

fn foo(string: &str) {

println("{:p}", string); // 0x5652d704aa80

}

fn main() {

let string = String::from("Hello, World!");

println("{:p}", string.as_ptr()); // 0x7efced01c010

foo(string);

}

fn foo(string: String) {

println("{:p}", string.as_ptr()); // 0x7efced01c010

}

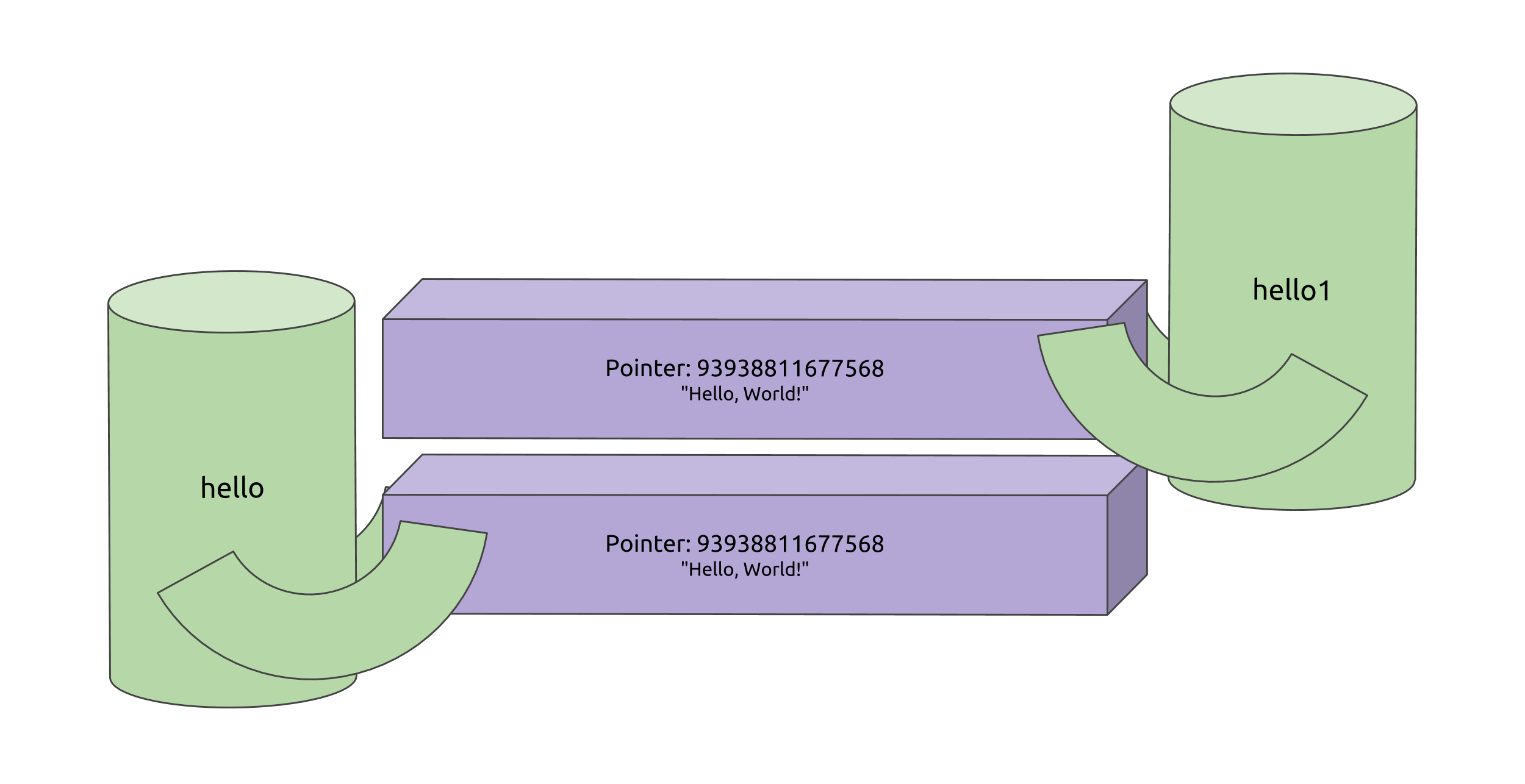

In the first example, we’re first passing a string literal, (which stores its data on the stack), into a function, foo(). In the second example, we’re passing a String type, (which stores it data in the heap), into a different function, foo(). In both implementations of main() and foo(), we print the memory address of the variable in their respective scopes.

In the first example, we see similar behavior to when we copied a variable’s value and bound it to a new variable. This happens because string literals use the stack; the size needed to store their pointers are known at compile time, and thus, we can easily copy it’s value and pop it onto the stack.

This means that each of the functions, main() and foo(), own their own copy of the of the pointer stored in string. When foo()’s scope is over, foo() is responsible for dropping it’s own string, and when main()’s scope is over, it too is responsible for dropping the string that it owns.

In the second example, on the other hand, main() is moving ownership of string into foo(). This means that main() no longer has ownership of the string variable, i.e. the place in memory that it points to. If we tried to accessing string from inside main() after it has been moved, we would receive an error.

Instead of copying, which could be expensive, Rust instead makes foo() responsible for the data in the memory address, 0x7efced01c010, as indicated in the comments of the example. Now, only when foo() goes out of scope will Rust free the memory at that address, and thus invalidate any other variables that have a pointer to that same address. Again, we do this to avoid a double free error.

Clone, redux.

For the second example, if we did want to copy the value of string, so that both main() and foo() own their own copies, similar to when using the string literal on the stack, we could make a “deep copy”, by using the clone() method:

fn main() {

let string = String::from("Hello, World!");

println("{:p}", string.as_ptr()); // 0x7efced01c010

foo(string.clone());

}

fn foo(string: String) {

println("{:p}", string.as_ptr()); // 0x7f89f841c028

}

Here, as indicated by the comments, main() and foo() have ownership of their respective copies of string. Although this is a valid solution, it is not the most efficient, since Rust needs to step through its heap allocation process each time. And sometimes you actually do want both functions to interact with the same piece of data! (More on that later).

Giving Ownership

Just as ownership is taken by calling another function and passing in a variable, a function can be given ownership via a return from a different function:

fn main() {

let string = foo();

println("{:p}", string.as_ptr()); // 0x7fc98be1c010

}

fn foo() -> String {

let string = String::from("Hello, World!");

println("{:p}", string.as_ptr()); // 00x7fc98be1c010

return string;

}

foo() now gives ownership to main() by returning string to where foo()was called. As expected, only when main()’s scope ends will Rust _free _0x7fc98be1c010.

Give & Take

If we follow this trend, it makes* *sense that we can both give ownership and then have that ownership returned to us by accepting and return the same String type in foo():

fn main() {

let string = String::from("Hello, World!");

println("{:p}", string.as_ptr()); // 0x7fc98be1c010

let string = foo(string);

println("{:p}", string.as_ptr()); // 0x7fc98be1c010

}

fn foo(string: String) -> String {

println("{:p}", string.as_ptr()); // 00x7fc98be1c010

return string;

}

But this seems like a lot of headache just to pass values in and out of functions. Luckily, this is a headache that the Rust maintainers have taken into account:

Taking ownership and then returning ownership with every function is a bit tedious. What if we want to let a function use a value but not take ownership? It’s quite annoying that anything we pass in also needs to be passed back if we want to use it again, in addition to any data resulting from the body of the function that we might want to return as well. Luckily for us, Rust has a feature for this concept, called references.

References & Borrowing

Ownership accommodates the sharing and passing of data, but, you’ve got to follow a few rules.

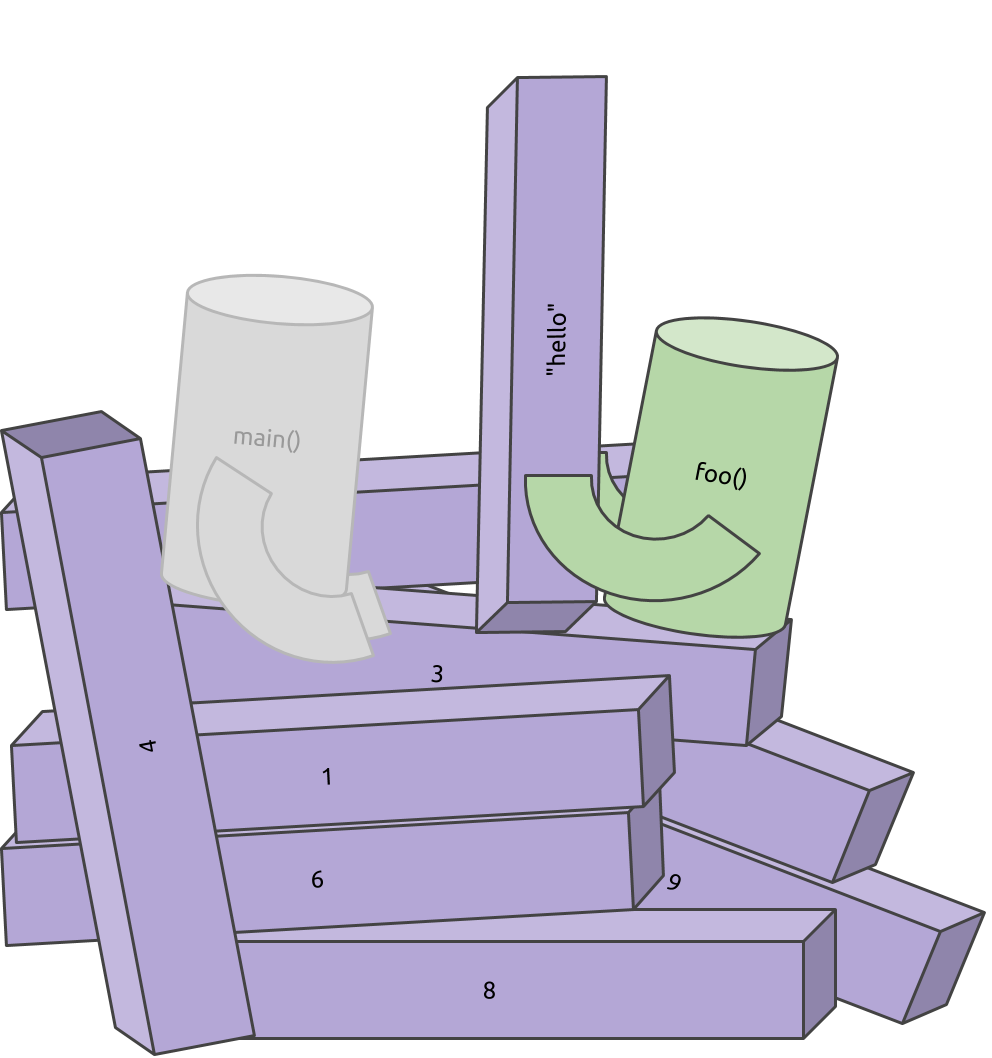

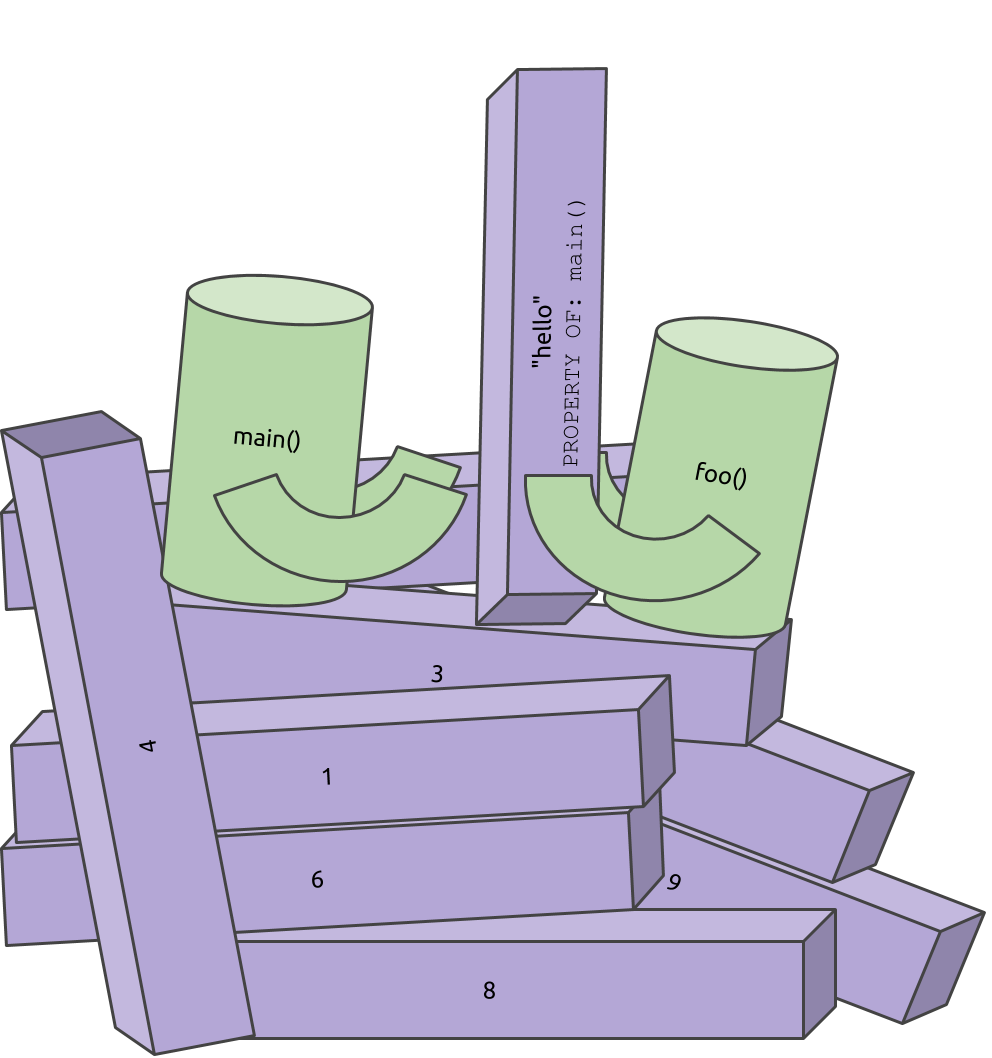

Borrowing looks like this:

main() gives foo() access to string, but, (as indicated by the label), main() is still the owner of string. This means that at the end of foo()’s scope, string will not be dropped from memory; main() is still responsible for string’s space in memory.

Here’s how we would write that interaction in Rust:

fn main() {

let string = String::from("Hello, World!");

println("{:p}", string.as_ptr()); // 0x7fc98be1c010

foo(&:string);

println("{:p}", string.as_ptr()); // 0x7fc98be1c010

}

fn foo(string: &String) {

println("{:p}", string.as_ptr()); // 00x7fc98be1c010

}

Just like our drawing, we would say that main() passes a *reference *of string into foo(), and foo() excepts a String type reference. This is indicated by & symbol. After then end of foo()’s scope, execution returns to it’s caller, main(), and string is still valid. foo() doesn’t have to return ownership, because it was never given ownership, it only borrowed.

Ampersands indicate references, which allow the passing of values without giving up ownership! Rust knows that when we’re passing a reference, the ownership, and therefore the responsibility of deallocating that space in memory, still belongs to the original owner.

Rust allows us to create any number of references:

fn main() {

let string = String::from("Hello, World!");

println("{:p}", string.as_ptr()); // 0x7fc98be1c010

foo(&:string);

println("{:p}", string.as_ptr()); // 0x7fc98be1c010

}

fn foo(string: &String) {

println("{:p}", string.as_ptr()); // 00x7fc98be1c010

bar(&string);

}

fn bar(string: &String) {

println("{:p}", string.as_ptr()); // 00x7fc98be1c010

baz(&string);

}

fn baz(string: &String) {

println("{:p}", string.as_ptr()); // 00x7fc98be1c010

}

No matter how many times we pass around a reference to string, ownership will return to it’s original owner. (In this case, ownership returns to the place where string was originally instantiated, but remember, we could have passed ownership and then created a reference).

Mutability

The last thing to mention is mutability. Rust is often written* *in a *functional* style, but the writers are very pragmatic and understand that modern languages aren’t always so black-and-white, thus Rust accommodates mutability.

fn main() {

let mut string = String::from("Hello, World");

println("{:p}", string.as_ptr()); // 00x7fc98be1c010

string.push_str("!");

println("{:p}", string.as_ptr()); // 00x7fc98be1d000

}

Rust allows us to use the mut keyword in order to make values mutable. Notice the change in memory address which indicates that string had to be reallocated in order to fit onto the heap.

Now that we have a mutable variable, we can make a mutable reference!

fn main() {

let mut string = String::from("Hello, World");

println("{:p}", string.as_ptr()); // 00x7fc98be1c010

foo(&mut string);

println("{:p}", string.as_ptr()); // 00x7fc98be1d000

}

fn foo(string: &mut String) {

println("{:p}", string.as_ptr()); // 00x7fc98be1c010

string.push_str("!");

}

The syntax here is a bit specific, but we see that first we need to declare a mutable variable let mut string. Then when we pass a mutable reference, using &mut. Finally, we use &mut in the function’s signature to explicitly state that our function accepts a mutable reference.

Now, we can still ensure that only main() is the responsibly for deallocating string, while also allowing other functions to mutate string!

Those familiar with memory management might think of how this can be dangerous if left unchecked. What happens if several functions hold a mutable reference and try to update the same memory location at the same time, asynchronously; like when using threads, for example? This leads to a data race condition.

A race condition occurs when two or more threads can access shared data and they try to change it at the same time. Because the thread scheduling algorithm can swap between threads at any time, you don’t know the order in which the threads will attempt to access the shared data. Therefore, the result of the change in data is dependent on the thread scheduling algorithm, i.e. both threads are “racing” to access/change the data.

This problem can be exacerbated when working with a low-level language, such as Rust. Rust allows us access to raw pointers, which may lend itself to a lot of unsafe scenarios.

This is the kind of thing ownership is set to protect against, and it does so by enforcing this rule: “at any given time, you can have either one mutable reference or any number of immutable references.”

The benefit of having this restriction is that Rust can prevent data races at compile time. A *data race *is similar to a race condition and happens when these three behaviors occur:

- Two or more pointers access the same data at the same time.

- At least one of the pointers is being used to write to the data.

- There’s no mechanism being used to synchronize access to the data.

Data races cause undefined behavior and can be difficult to diagnose and fix when you’re trying to track them down at runtime; Rust prevents this problem from happening because it won’t even compile code with data races!

Rust’s ownership rules come to the rescue again, which is emphasized as the core safety feature that Rust provides over other systems languages. This means that Ruby programmers, like myself, still don’t have to be intimately acquainted with the inner-working of memory management!

Dangling References

One last thing, when passing references, there is another condition what can cause bugs called dangling references.

Dangling references are pointers to data that has been deallocated, for example:

fn main() {

let string = foo();

}

fn foo() -> &string {

let string = String::from("Hello, World!");

println("{}", string);

&string

}

In this example, foo() returns a reference to string. However, once foo()’s scope ends, the memory for string is deallocated, which means the reference will point to a invalid place in memory!

Rust prevents this at compile time by throwing an error.

error[E0106]: missing lifetime specifier

- --> src/main.rs:110:13

|

5 | fn foo() -> &String {

| ^ expected lifetime parameter

|

= help: this function's return type contains a borrowed value, but there is no value for it to be borrowed from

Rustaceans can enjoy the benefits of the ownership model without understanding the protections it provides. However, being able to comprehend the problems that ownership solves only helps to write better code without fighting against the compiler.

There’s still a bit more left to uncover about Rust ownership, but with these two posts, hopefully you’re left with enough to get started working with this elegant solution to an otherwise unwieldy problem.